This is part 2 of a series that is taking a closer look at spatial computing and how it is a pivotal component in driving us towards web 3.0 and the metaverse.

If you haven’t already read part 1, it is available here.

Much of the attention surrounding the metaverse has been centred around social experiences and entertainment. But, much like the early adoption of computers were driven by businesses, I believe that industrial and enterprise use cases will be pivotal in driving the technology surrounding web 3.0 and the metaverse.

The goals of the ‘industrial metaverse’ are not about social interaction or entertainment, but about using virtual and augmented worlds to make actions in the real world better, or to be candid – to make material difference on an organisation’s top and bottom line. This can be in the form of training personnel, to transforming the way in which physical assets are created, built and operated.

Wait, but haven’t we used simulations for training and manufacturing for years?

Simulations have been used for training purposes for many years. CAE pioneered the use of simulators for pilot training on commercial aircrafts. Back in the 70s these looked like below…

(Source: CAE)

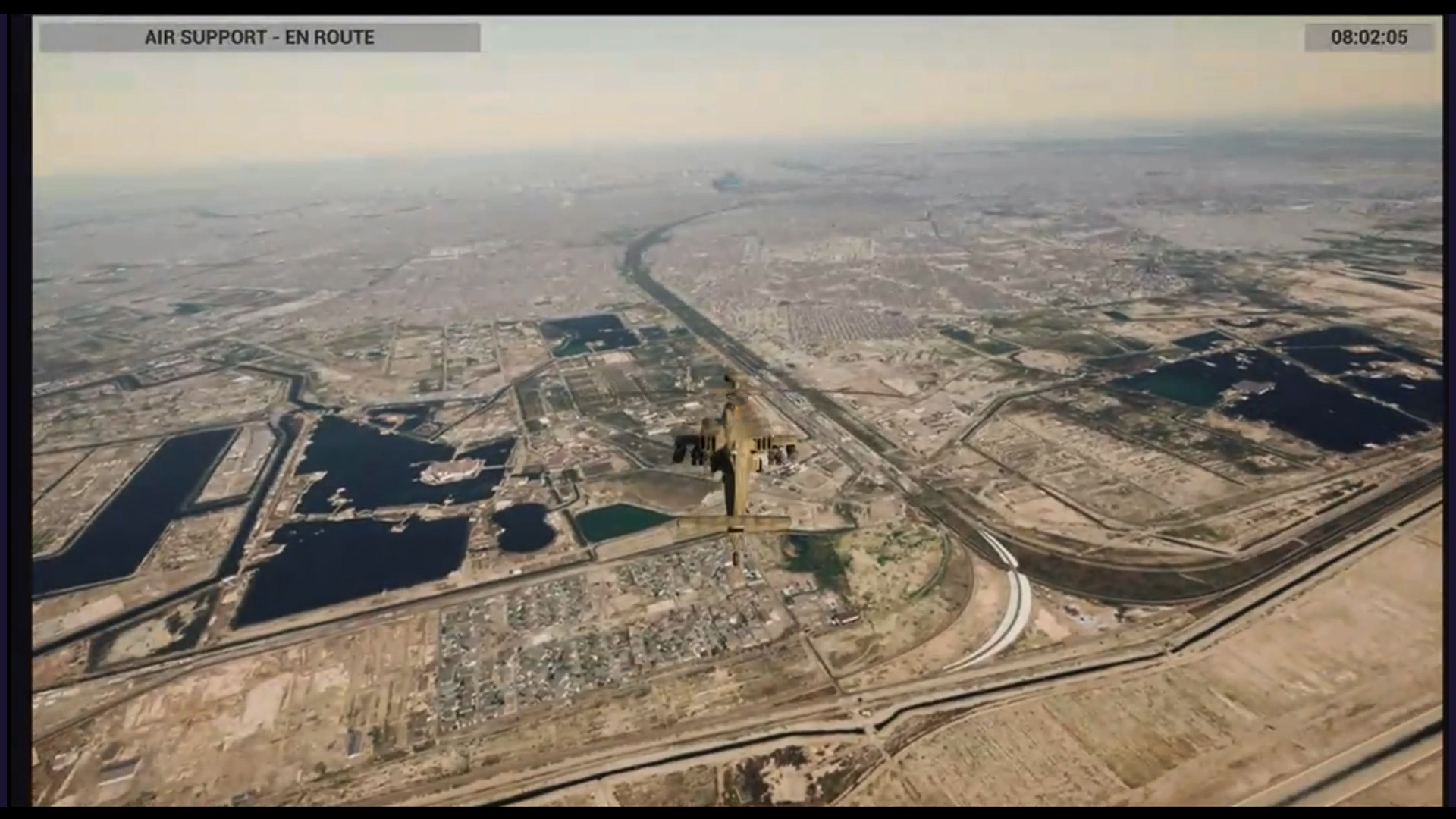

As technology evolved, the goal has been to democratise and distribute these training capabilities, making it more accessible than fixed hardware simulators with even greater accuracy, fidelity and interoperability with other systems. Microsoft’s Flight Simulator is a great example of how these capabilities have come on in leaps and bounds, with ultra-realistic simulations that can truly question what is real and what is not…

(Source: Microsoft Flight Simulator vs Real Life)

More accessible flight simulators such as GeoFS can be used for free, via web browsers and mobile phones. Enabled through integrations with external data sources (such as Cesium and Bing Maps) whilst leveraging the power of the community to add a whole roster of different aircrafts.

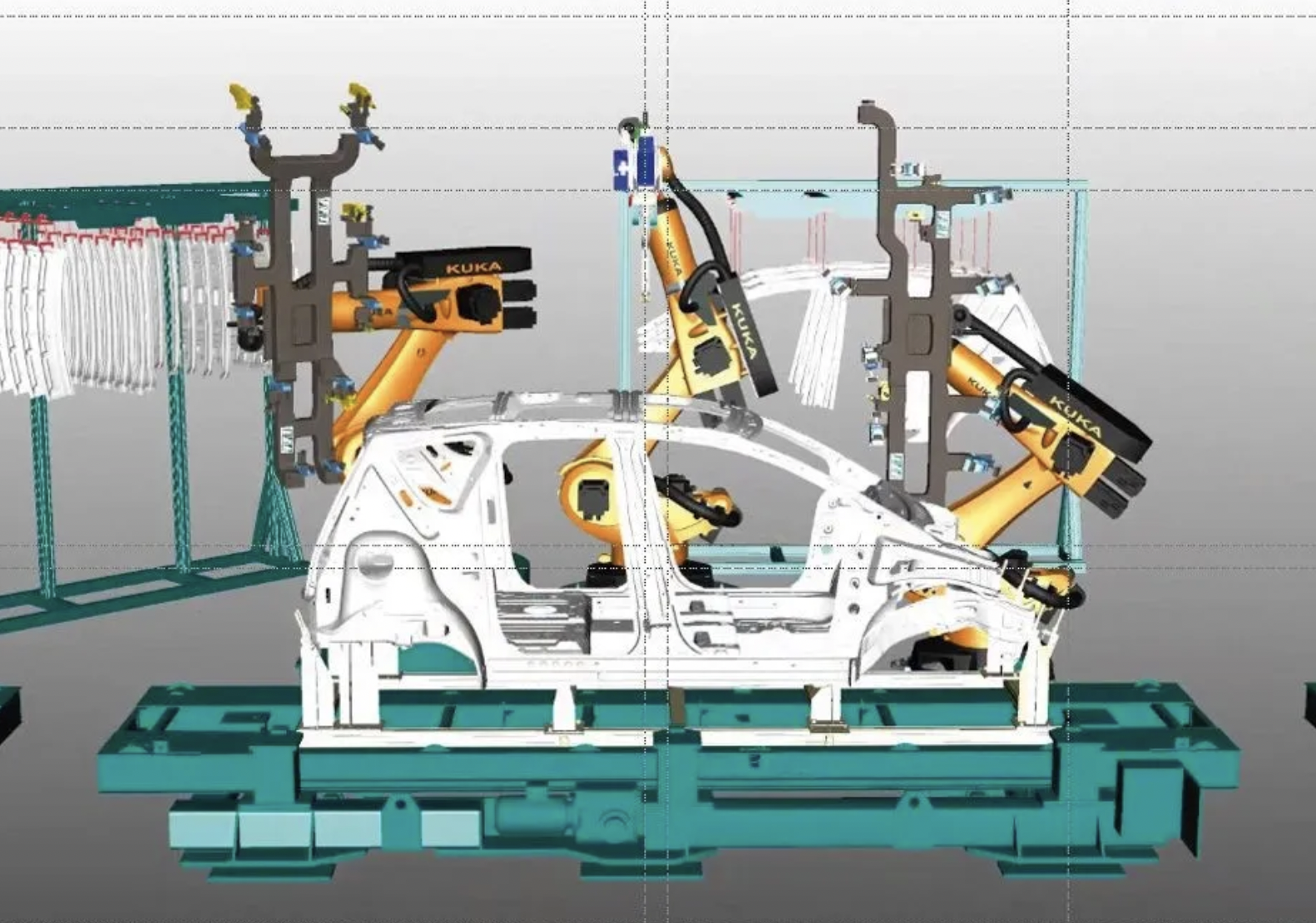

Within the world of manufacturing, a good example of how such interoperability and integrations has fostered greater applicability is how Computer Aided Designs (CAD) amongst other design formats are now used in game engine simulations. Like simulator training, CAD has been around for many years to technically design and test physical assets. They are now increasingly used alongside game engines to create more interactive product demonstrations and visualisations.

Datasmith optimises importation and transferability of external design formats

into Unreal Engine

(Source: Unreal Engine Datasmith)

What does this have to do with the metaverse?

By combining different classes of data and simulations together we are able to form environments that are composed in layers, allowing separate physical and abstract systems to connect and function together. For example, we could have a city-scale simulation that includes layers of traffic, finance, and critical infrastructure such as electricity and water.

City scale simulation

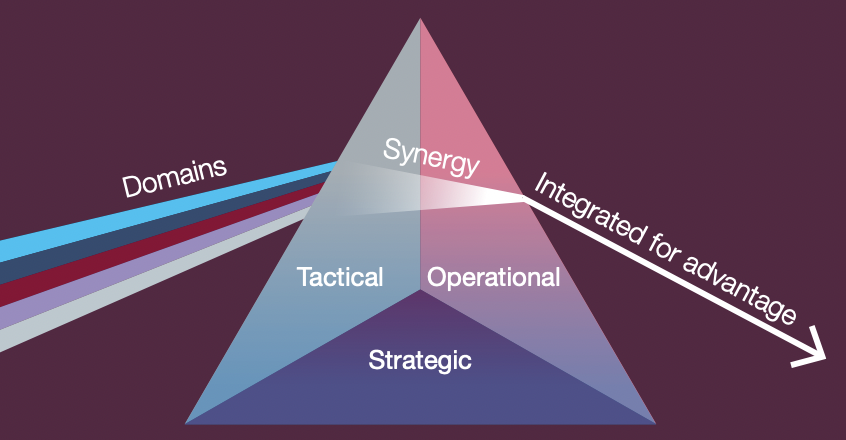

We are seeing the demand for these environments in the Defence industry where governments and systems integrators are looking towards ‘single synthetic environments’ that are able to form a ‘digital backbone’ and enable federated exchange of information and facilitate training activities between different forces and countries.

Multi-Domain Integration (Source: MoD)

Combining these scalable training environments and simulations with real world data using 5G and IoT creates a virtuous feedback loop between the physical and virtual worlds – introducing a set of scenarios that can be analysed and studied by AI systems. This in turn will lead to improvements in the real world, for a whole range of use cases. It will enable an ecosystem of information for on-going insights, analytics and scenario simulation.

These concepts are somewhat analogous to the term Digital Twins that many of us have heard in the enterprise sector over the last few years: virtual copies of real-world systems that combine data sets across multiple sources to simulate the behaviour of a system, as it would perform in the real world. The differences between the metaverse and digital twins is not well defined, but I like to think that digital twins usually represent a system for a specific purpose, whilst the metaverse is an all encompassing simulation environment that is holistic and can be layered, used by multiple stakeholders.

Siemens Digital Twin Schematic (Source: Siemens)

Of course it is not just ‘industrial’ use cases, we are seeing virtual workplaces and events. As mentioned in part 1, there is an influx of investment in building the tools for a more decentralised workforce. One of our partners, PixelMax is doing exactly this – building immersive virtual space that enables employees and wider communities to effectively communicate, collaborate and co-create, regardless of location.

PixelMax Virtual Workspace (Source: PixelMax)

All of these applications share common capabilities of spatial computing at large scale, and an open approach to architecture that enables multiple data sets and virtual worlds to coalesce into one. And although these use cases are somewhat different to the social metaverse that most us are better acquainted with, the technology and constituent parts are very similar.

The metaverse is in its infancy, and it will take shape over the years to come through a lot of experimentation. It will be transformational for the organisations that embrace it, with a number already investing heavily and getting a head start. Often referred to as the open metaverse, it will take organisations to move from centralised models to a more open and collaborative architecture to foster trust and ownership amongst communities and stakeholders. It is a shift that we are observing across the spectrum as we transition to web 3.0.

We will explore these aspects further in Part 3: Decentralised Architectures and the Open Metaverse.

———–